Breathe Now is a song of hope in the face of adversity and oppression.

Building on a familiar hymn tune, its words are inspired by Martin Luther King, his dream, his determination, and his use of biblical imagery to energize the pursuit of equality and justice.

Breathe Now

A song of hope in the face of adversity and oppression

Martin Luther King

Today, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. may be regarded as a national hero, and each year he is celebrated on MLK day, a federal holiday. However, I suspect that many people may claim to admire King without fully understanding his ideas or without fully knowing the principles for which he stood. In looking at King’s speeches, several key features stand out. These are features that, today, may be rarely combined and rarely viewed as belonging together. Today, when people think about King, they may miss some of these key features. They may paint him in a way they want him to be, in a way that makes them feel good, or in a way that fits their own perspective. But, I think King’s message is especially moving and persuasive when we consider all its features and we are able to view it as it actually is.

Common ways that we misunderstand Martin Luther King

I have admired King for most of my life, but I am realizing how I have often admired King in ways that were constrained by my own perspective, which in my case, is the perspective of someone with white skin. For example, I have often admired King for the way he advocated for nonviolence – how he advocated for civil disobedience and protest without hostility, without weapons, and without physical assault. However, I must confess that maybe this non-violent approach was especially appealing to me because it was less threatening than other more violent alternatives. Also, I have sometimes been tempted to view King as the leader of a victorious civil rights movement that ended a terrible history of racial segregation in the South, and this perspective runs the risk of ignoring or downplaying the racism and oppression that still exist today. Other times, I have been tempted to idealize King almost as if he were a superhero, ignoring the fact that he was a human being with faults – as if I need King to demonstrate an unrealistic level of super-human perfection in order for his ideas to be justified or for oppressed people to earn the right for equality. On the one hand, it is true that King advocated for non-violence, that he led a movement that achieved several victories over southern segregation, and that he deserves to be admired and honored. On the other hand, if we place too much emphasis on these particular themes we may end up with a distorted, diluted, or even counterproductive view of his message.

Three key features

What, then, will give us an accurate perspective? What are the key features of King’s message – the features on which we need to focus to understand his ideas and the principles for which he stood? What are the themes in his work that may be especially important for us to understand today? In looking at King’s life and his speeches, three key features stand out. These include: (a) religious fervor, (b) political activism for justice and equality, and (c) hope for the future. Today, this may seem like an odd mix of ideas. Many people who claim to have religious fervor take actions that seem to hinder progress toward justice and equality. Many people who advocate for justice and equality do not claim to draw their inspiration from religion. And, regardless of viewpoint, many people focus more on dehumanizing and hating their enemies rather than on instilling hope for the future. However, when these three features – involving religion, activism, and hope – are all put together, as King did with great skill, it makes the message especially compelling. How, then, did King put these features together and why is this important?

Religious fervor

King was a Baptist Christian minister, a man of religious fervor, and biblical imagery was woven through most of his speeches. He studied for the ministry at Crozer Theological Seminary, completed a doctoral degree in theology at Boston University, served several years as pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, then moved to Georgia where he served for the remainder of his life as co-pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. King identified himself as a pastor. His faith and his civil rights activism were intertwined – they were one and the same. When he preached, he talked about civil rights; and when he talked about civil rights, he was preaching.

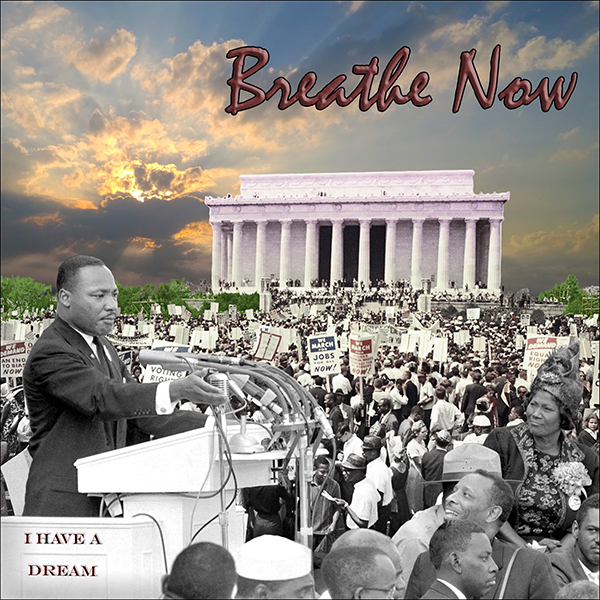

When King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, he was a pastor preaching a sermon. Clarence B. Jones tells the story of watching King give this speech. He recalls how seated up front near to King was Mahalia Jackson, who was a famous gospel singer and King’s good friend (she can be seen on the right-hand side of the collage image for this post). Although King did not start off talking about his dream, she interrupted King during the speech and said, “Tell them about the dream, Martin. Tell them about the dream.” Jones recalls how King then shifted his posture to a preaching stance, and Jones remembers turning to the person next to him and saying, “these people don’t know it, but they are about ready to go to church.” Similarly, in recalling King’s speech, Representative John Lewis once said, “When he spoke that day on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, he was preaching.” Thus, one crucial thing to know about King is that he saw himself as a pastor, and for him, addressing civil rights was a deeply religious experience.

Importantly, King’s religious fervor was progressive and inclusive in nature.

King was progressive and inclusive in his religious fervor. His dream was for the reconciliation of all people, not judgment. He valued multiple religious perspectives, holding special admiration for the Hindu leader Mohandas Gandhi, and King claimed his ideas were consistent with what he called, “Hindu-Muslim-Christian-Jewish-Buddhist belief.” In line with King’s religious fervor, his speeches were filled with biblical references, and in line with his progressive approach, he used what I call an “inspirational” style of biblical interpretation. That is, instead of using biblical texts to extract a single, authoritative, literal, historical meaning, he used biblical texts to provide images, metaphors, and ideas that inspire us and move us toward something good (for more on the difference between authoritative and inspirational approaches to biblical interpretation, see the post for the song, Meanings).

Examples of how King used this inspirational type of biblical interpretation are found in his “I Have a Dream” speech. Specifically, this speech contains two especially vivid Biblical references. First, he quotes the book of Amos (5:24) where he says, “We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.” Second, he quotes the book of Isaiah (40:4) where he says, “I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.” Notably, his use of these passages was not rigid or literalistic. He changed a few words, and he gave these passages new meaning. Historically, the Isaiah passage originally pertained to an exiled people waiting for divine intervention to restore their homeland, yet King used it to inspire and motivate people to take action in a modern struggle against racism. Whereas some conservative Christians have argued that the Isaiah passage’s “true” meaning involves a prediction of Jesus, King used this passage in a way that did not require it to have any singular “true” meaning. The function of this passage was not to delineate an orthodox religious creed, but to draw from a deeply religious experience to create an inspirational vision that energized a modern civil rights movement.

The biblical passages that King used in his speeches were part of his internalized religious foundation.The passages he used were something he studied and knew so well that they became fused with his way of viewing the world. In his “I Have a Dream” speech, his biblical quotations were seamlessly woven into his speech such that people unfamiliar with these passages might not even realize they were biblical quotations. King did not use these passages to establish rules for religious doctrine, but instead, they were something so familiar and so intimate that they were part of his natural way of thinking and speaking and they inspired his vision for the world. On the one hand, King’s fervor was certainly not that of an authoritarian or fundamentalist type of religion. On the other hand, King’s fervor was still deeply religious.

In sum, part of what made King’s leadership and civil rights activism especially powerful is that his work was infused with a religious fervor. Today, some people working to promote civil rights may seek to take a more secular, non-religious approach. Often, this is appropriate; however, I wonder if sometimes it may be a mistake. When the movement is infused with a faith perspective, it takes on a power and fervor. It draws from something deep. It becomes more than a mere opinion, more than a political movement, more than an expression of anger, and more than an academic position. It becomes a movement seeking a type of goodness that gives meaning to life and that imputes value on the struggle. It draws from something that transcends human experience to promote a type of goodness that is woven through the fabric of the universe. Sometimes religious fervor is important because it provides hope and inspiration.

Political activism for justice and equality

In addition to being driven by religious fervor, King’s pursuit of justice and equality was highly political. He took actions based on political calculation and he engaged with political leaders. His speeches included frequent patriotic themes with references to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. For example, in his “I Have a Dream” speech, he talked about, “the architects of our republic,” who “wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence,” and how these words, “guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Today, when faith and politics are combined, it is often part of a more conservative agenda. However, King took faith and religion and combined it with patriotism and politics to focus on civil rights and social justice.

As a political activist, King took a strong stand on controversial political issues.

Recently, I have heard some (mostly White) people condemn current civil rights protesters for not being like King, and I suspect these people are unaware of the actual political positions that King took. I suspect that many (mostly White) people today praise King without knowing the positions he supported. For example, he called for protest against police brutality (which then as now, was a controversial topic), and in his “I Have a Dream” speech, he advocated for those, “staggered by the winds of police brutality.” Elsewhere, King talked about riots against police and against racism, and he described these riots not as something to be condemned, but as the, “language of the unheard.” In response, he talked about the need for the United States government to enact legislation to address issues of unemployment, poverty, and inequality, saying, “We must develop massive action programs all over the United States of America.” He promoted the idea of, “a guaranteed minimum income for all people and for all families of our country.” Regarding other political topics, he spoke out strongly against the Vietnam war, called attention to racial disparities in soldier deaths, and called for defunding the military to increase spending on social welfare programs. When the conservative Republican candidate Barry Goldwater lost the 1964 presidential campaign, King said, the American people “revealed great maturity” by rejecting a candidate identified with “racism” and the “radical right.” Thus, King clearly took strong political positions that, both then and today, some may regard as controversial.

If King were alive today, he would almost certainly continue to take these same types of political positions. He would almost certainly say that we still have profound problems with racism, oppression, and injustice. He would remind us that these issues have not gone away. I suspect he would say we have made some steps forward in some areas but made some steps backward in other areas. In his speeches, King made a distinction between the fight against Southern segregation, which he described as just one, specific, especially ugly type of discrimination, and the larger struggle for genuine equality, which he described as being much more difficult. He said, “It is much easier to integrate a lunch counter than it is to guarantee a livable income and a good solid job.” Part of the difficulty was that some people (especially White people in the North) could easily see the ugliness of Southern segregation, and condemn it, while at the same time denying or ignoring larger, systemic problems regarding racism and injustice. Although King led a movement that ended some forms of Southern segregation, this was just one piece of his larger goal to achieve justice and equality, and today, that larger goal still remains a long way off.

King’s approach involved an activism that many viewed as disrespectful or troublesome.

Although King's approach was nonviolent, he certainly was not passive. He was an agitator. He caused troubles. He stirred the waters. He did things and said things regarded as controversial. Today, some may be tempted to believe a myth, thinking that most people in 1960s United States admired the work of King, and that it was only southerners, or only a minority of overtly racist people, who hated him. This was clearly not true. In the 1960s, most people in the United States (especially White people) disliked King and viewed him as an extremist, troublesome, agitator. Both democrats and republicans alike commonly accused King of being a communist. After the March for Jobs and Freedom in Washington D.C. where King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, President Kennedy viewed King as dangerous and approved an FBI plan to monitor him, a program that included extensive tapping of King’s private phone conversations. At that time, a Gallup poll indicated that only 20 percent of the United States viewed King’s march in Washington as something good. Some worried it would start a race war, and a majority simply thought those attending the march were being disrespectful and ungrateful. A few years later, a poll found that over 70% of Americans had a negative view of King. Thus, the people who are best following King’s example today are probably those who agitate and those who engage in action and protest that others are likely to label as disrespectful, troublesome, or controversial.

Hope for the future

One of the most striking features of King’s message is that, despite the opposition he faced, he maintained a consistent message of hope. His message never slipped into themes of cynicism, hate, or despair. He expressed a religious faith that produced hope, even confidence, that, one day, things will be made right. This hope was clearly expressed in his “I Have a Dream” speech. Indeed, this was a speech that focused on hope – a dream for a future when “all of God’s children” will join hands and sing, “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!” Elsewhere, he connected this dream and hope with a faith that inspires political action, saying with “faith we will be able to speed up the day” when this dream is realized. After being awarded a Nobel prize, he gave a speech in which he proclaimed his confidence that, “Oppressed people cannot remain oppressed forever,” and then he connected this belief with the Bible’s “thrilling story of how Moses stood in Pharaoh’s court centuries ago and cried, Let my people go.” Thus, he both expressed strong hope and connected this hope with religious faith. In one of his most profound expressions of this hope, King said,

The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.In other words, King had confidence that, although the fight may be long and difficult, eventually, someday, society will certainly move toward justice and equality; therefore, it is worthwhile and effective to continue the fight. This hope that King professed is highly motivating. It provides a reason for determination, for persistence, a reason to persevere even when things seem bleak, even in the face of overwhelming opposition.

There was a strong connection between the hope that King held and his reason for advocating for nonviolent resistance. To some extent, part of the reason he advocated for nonviolence was simply because he believed it was the most effective method to use. But also, his nonviolent approach was consistent with his hope, which in turn was tied to his faith. His dream was for a world characterized by love, justice, and equality. It was a vision that he found in the Christian Bible, which contains many passages that speak to issues of social justice, of deliverance for oppressed people, of people demonstrating love for one another, and of peace. Thus, nonviolent tactics best fit with King’s ultimate hope for the type of society he sought to achieve. Accordingly, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, he said, “We adopt the means of nonviolence because our end is a community at peace with itself.” In other words, nonviolence, in and of itself, was not the primary goal or objective. The goal was to reduce hatred and achieve equality.

King's view of nonviolence only makes sense if we share his hope.King's view of nonviolence only makes sense if we see profound problems with racism and inequality, if we are engaging in political activism to address those problems, and if we are moved by religious fervor to hope for a world characterized by love, justice, and equality. We correctly understand King’s message if we feel personally challenged to humanize our own enemies and if we feel personally challenged to hope for reconciliation with those who hate us. We distort his message into something racist if we point a judgmental finger at an oppressed people and accuse them of using too much violence. If we do not see the injustice, or if we are not engaging in activism ourselves, then taking a stance for nonviolence becomes an insensitive, racist, judgmental attitude toward an oppressed people. Unfortunately, there is a potential danger in King’s message in that it can be easily distorted in this way. At the same time, if his hope is proclaimed with the respect it deserves, if people fully understand the rationale and the agenda, if they are truly seeking to fight racism and injustice, then it has the potential to be an especially uplifting and inspiring type of hope.

King’s final speech

These features involving religious fervor, political activism, and hope are evident in the final speech King gave in 1968 on the day before he was assassinated. This speech was a sermon King gave at the Charles Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee, as part of a trip in support of sanitation workers who were on strike. Consistent with his use of patriotic themes, King talked about First Amendment rights, saying, “But somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read (Yes) of the freedom of speech. (Yes) Somewhere I read (All right) of the freedom of press.” Then, consistent with how he combined religious ideas with political activism, King told the story of Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan and he used it to call people to support the sanitation worker strike and to boycott targeted businesses, challenging them to ask the question, “If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?” Then, King ended his speech drawing a clear allusion to the biblical story of how Moses, just before his death, viewed from a mountain top the promised land his people would soon enter. In lines that seemed to predict his own death, King said:

[God] has allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.Thus, King concluded his last speech with a profound expression of his hope, of his determination, of his confidence that, although the fight may be long and difficult, the arc of the moral universe does indeed bend toward justice.

Indeed, there is much to admire in King, and we may best be able to learn from him and to continue his fight for justice and equality if we have a full understanding how the key components of his message were intertwined. For King, these components worked together and were dependent on each other. Without the political activism, the faith and the hope become meaningless empty shells. Without the religious fervor, the activism and the hope would lose the inspirational vision that empowers, guides, and motivates them. Without the hope, it would be difficult to sustain the religious fervor and the political activism. Thus, from the perspective of King, we need all three: religious fervor, political activism, and hope.

Breathe Now

The lyrics for the song, Breathe Now, are inspired by King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and the tune is drawn from the well-known hymn, “Finlandia” (which is a tune taken from a symphonic poem by Jean Sibelius in 1899 and used in several hymns such as “Be Still my Soul” and “We Rest on Thee”). The song draws from King’s dream and his hope with the words, “Dream now the dream that stops the storms of strife.” It includes allusions to some of the key phrases from King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, with lines such as, “When all God’s children then join hands to sing / We’re free at last,” and, “Hew from the mountain of a great despair / A stone of hope.” The song also draws from the same biblical passages that King quoted in his speech, including a line drawn from Amos (5:24), “May justice roll like waters in a stream,” and a line drawn from Isaiah (40:4) “When mighty mountains hear the tender cry, and every valley lifted to the sky.”

The song Breathe Now, also includes allusions to apocalyptic biblical passages that were not specifically used by King (to my knowledge), but that are used in the song like the way that King used biblical imagery as a source for inspiration. For example, drawing from biblical passages with apocalyptic words spoken by Jesus (such as in Matthew 24:29), it includes the line, “For in these days, the sun may cease to shine / and stars grow dark as peace fades in decline.” Also, drawing from the apocalyptic book of Revelation where a great dragon is described as seeking to devour a mother’s newborn child, it includes the line, “And when a dragon storms across the earth / to hate the child a mother brings in birth.” For people facing political oppression, racism, or any other form of adversity, these passages provide vivid imagery that help capture and express the human experience. Sometimes it feels as if the sun has ceased to shine, stars have gone dark, peace has disappeared, and as if a mighty dragon seeks to devour a newborn infant. Because these passages capture the human experience, they draw us into the message, which is a message of hope and encouragement to stand firm in the face the adversity.

Like the way that King weaved biblical passages into his speeches, these apocalyptic passages as used in the song are not intended to be heard as something rigid or literalistic. Instead, they are intended to create inspirational imagery and they are allowed to take on new meanings. When these passages were first written, the authors may have had in mind an imminent apocalyptic supernatural overthrow of the Roman government and the establishment of God’s kingdom and justice here on earth. For the author of Revelation, the dragon probably symbolized the Roman empire, but for us today, this image can inspire many meanings. The dragon could be any form of injustice or oppression. It could be racism, or it could be viewed as a reference to the Grand Dragon title given to leaders in the Ku Klux Klan. (And, although I have been focusing on issues of equality and justice, the dragon could certainly also represent other forms of adversity, such as a pandemic that storms across the earth.) Thus, the song Breathe Now follows King’s example, and it draws from biblical passages to produce inspiration. These passages can produce vivid imagery that energize the pursuit of equality and justice.

Comments

Thank you for this!

How could I get permission to use your text as a hymn for a worship service? (I find singing it moves me and my congregation more than only listening.)

You are welcome to use the text (or anything else at the ForwardFaith website) in a worship service, and I would feel honored if you did so. Thank you for your interest.

Great lyrics and accompanying explanation. Finlandia was a good choice for the music.

I found that for my 80 year old ears the country music presentation style was difficult to follow. Instruments masked the lyrics. Full disclosure, I have the same problem with most contemporary hymns.

You might have some church choirs to record it with organ music. That style may resonate better with older folk. You could even interlace black, white, and mixed church choirs.